As they thunderheads drifted far to the east, whistlers were heard a couple seconds after the appearance of every distant lightning flash. A line of passing thunderstorms provided a bounty of crackles and tweeks early on. I heard all the phenomena described above. Saturday night was a bonanza for natural radio. Click on the links above to hear the different sounds.

#Wr 3 vlf receiver full

Sometimes there are swooshing sounds, but chorus primarily sounds like a pond full of peeping frogs or a flock of birds singing at sunrise.

When conditions are right, a VLF receiver can pick up disturbances in Earth's magnetic bubble spawned by auroras called ' chorus' or 'dawn chorus'. Sometimes you'll hear dozens of whistlers one after the other. Tweeks are very brief whistlers last anywhere from 1/2 to 4 seconds or longer.

#Wr 3 vlf receiver series

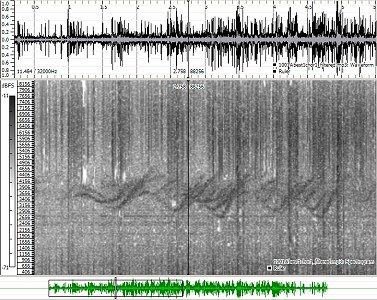

What you hear are a series of descending whistles that remind me of the whistling sound of bombs released from a plane like you'd see in a World War II movie. After their long journey, the higher frequency waves arrive before the lower frequency ones causing them to spread out in tone. When those same lightning radio waves enter Earth's magnetosphere and interact with the particles there, they can cycle back and forth between the poles traveling tens of thousands of miles to create what are called whistlers. Flurries of tweeks have an almost musical quality like someone plucking the strings of a piano. When that energy gets ducted through the upper layers of Earth's atmosphere called the ionosphere over distances of several thousand miles, it emits another type of sound called ' tweeks' which remind a listener of pings or dripping water. Lightning gives off lots of energy in the long end of the radio spectrum. The first thing you hear will be the pops, crackles and sizzles of distant lightning called sferics which are similar to what you've probably heard on your car radio during a thunderstorm. They're great absorbers of the low frequency radio energy you're trying to detect. I drive out to a open 'radio quiet' rural area, turn on the switch and raise the antenna to the sky. You'll need to be at least a quarter mile from any of those sources in order to hear the more subtle music of the planet. It creates a loud, continuous buzz in the headphones. The receiver picks up lots of things besides aurora including a big 'unnatural' hum from alternating or AC current in power lines and home appliances. Plug in a set of headphones and you're ready to listen. The on-off switch also controls the volume. The components are housed in a small metal box with a whip antenna and powered by a 9-volt battery. I fire up a little unit called a WR-3 that I bought for $60 back in the mid-1990s. Radio waves given off by auroras and other forms of natural 'Earth energy' like lightning range from 19 to 1,800 miles long or longer! To make them available to our senses we use a radio receiver. The pigments in our retinas convert these waves into visible images of the world around us. We're used to waves of light which are very, very short, measuring in the millionths of an inch long.

This handheld device converts very low frequency radio waves produced from the interaction of the solar electrons and protons with the Earth's magnetic field into sounds you can listen to with a pair of headphones. If you're like me and hard of auroral hearing, a small VLF radio receiver will do the job nicely. Given that the aurora is never closer to the ground than 50 miles, the air is far too thin to transmit any weak sound waves that might be produced to your ears. It's a psychological thing - you see a spectacular display of auroral light and in your head hear sounds your imagination might expect like crackling and whooshing. Of course another reason people might hear auroras is they imagine a soundtrack.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)